Functions

A function is an independent section of code that maps zero or more input parameters to zero or more output parameters. Functions (also known as procedures or subroutines) are often represented as a black box: (the black box represents the function)

Until now the programs we have written in Go have used only one function:

Until now the programs we have written in Go have used only one function:

func main() {}We will now begin writing programs that use more than one function.

Your Second Function

Remember this program from chapter 6:

func main() {

xs := []float64{98,93,77,82,83}

total := 0.0

for _, v := range xs {

total += v

}

fmt.Println(total / float64(len(xs)))

}

This program computes the average of a series of numbers. Finding the average like this is a very general problem, so it's an ideal candidate for definition as a function.

The average function will need to take in a slice of float64s and return one float64. Insert this before the main function:

func average(xs []float64) float64 {

panic("Not Implemented")

}Functions start with the keyword func, followed by the function's name. The parameters (inputs) of the function are defined like this: name type, name type, …. Our function has one parameter (the list of scores) that we named xs. After the parameters we put the return type. Collectively the parameters and the return type are known as the function's signature.

Finally we have the function body which is a series of statements between curly braces. In this body we invoke a built-in function called panic which causes a run time error. (We'll see more about panic later in this chapter) Writing functions can be difficult so it's a good idea to break the process into manageable chunks, rather than trying to implement the entire thing in one large step.

Now let's take the code from our main function and move it into our average function:

func average(xs []float64) float64 {

total := 0.0

for _, v := range xs {

total += v

}

return total / float64(len(xs))

}Notice that we changed the fmt.Println to be a return instead. The return statement causes the function to immediately stop and return the value after it to the function that called this one. Modify main to look like this:

func main() {

xs := []float64{98,93,77,82,83}

fmt.Println(average(xs))

}Running this program should give you exactly the same result as the original. A few things to keep in mind:

The names of the parameters don't have to match in the calling function. For example we could have done this:

func main() { someOtherName := []float64{98,93,77,82,83} fmt.Println(average(someOtherName)) }And our program would still work.

-

Functions don't have access to anything in the calling function. This won't work:

func f() { fmt.Println(x) } func main() { x := 5 f() }We need to either do this:

func f(x int) { fmt.Println(x) } func main() { x := 5 f(x) }Or this:

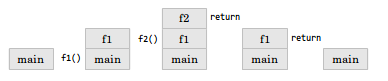

var x int = 5 func f() { fmt.Println(x) } func main() { f() } Functions are built up in a “stack”. Suppose we had this program:

func main() { fmt.Println(f1()) } func f1() int { return f2() } func f2() int { return 1 }-

We could visualize it like this:

Each time we call a function we push it onto the call stack and each time we return from a function we pop the last function off of the stack.

We can also name the return type:

func f2() (r int) { r = 1 return }

Returning Multiple Values

Go is also capable of returning multiple values from a function:

func f() (int, int) {

return 5, 6

}

func main() {

x, y := f()

}Three changes are necessary: change the return type to contain multiple types separated by ,, change the expression after the return so that it contains multiple expressions separated by , and finally change the assignment statement so that multiple values are on the left side of the := or =.

Multiple values are often used to return an error value along with the result (x, err := f()), or a boolean to indicate success (x, ok := f()).

Variadic Functions

There is a special form available for the last parameter in a Go function:

func add(args ...int) int {

total := 0

for _, v := range args {

total += v

}

return total

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(add(1,2,3))

}By using ... before the type name of the last parameter you can indicate that it takes zero or more of those parameters. In this case we take zero or more ints. We invoke the function like any other function except we can pass as many ints as we want.

This is precisely how the fmt.Println function is implemented:

func Println(a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)The Println function takes any number of values of any type. (The special interface{} type will be discussed in more detail in chapter 9)

We can also pass a slice of ints by following the slice with ...:

func main() {

xs := []int{1,2,3}

fmt.Println(add(xs...))

}

Closure

It is possible to create functions inside of functions:

func main() {

add := func(x, y int) int {

return x + y

}

fmt.Println(add(1,1))

}add is a local variable that has the type func(int, int) int (a function that takes two ints and returns an int). When you create a local function like this it also has access to other local variables (remember scope from chapter 4):

func main() {

x := 0

increment := func() int {

x++

return x

}

fmt.Println(increment())

fmt.Println(increment())

}increment adds 1 to the variable x which is defined in the main function's scope. This x variable can be accessed and modified by the increment function. This is why the first time we call increment we see 1 displayed, but the second time we call it we see 2 displayed.

A function like this together with the non-local variables it references is known as a closure. In this case increment and the variable x form the closure.

One way to use closure is by writing a function which returns another function which – when called – can generate a sequence of numbers. For example here's how we might generate all the even numbers:

func makeEvenGenerator() func() uint {

i := uint(0)

return func() (ret uint) {

ret = i

i += 2

return

}

}

func main() {

nextEven := makeEvenGenerator()

fmt.Println(nextEven()) // 0

fmt.Println(nextEven()) // 2

fmt.Println(nextEven()) // 4

}makeEvenGenerator returns a function which generates even numbers. Each time it's called it adds 2 to the local i variable which – unlike normal local variables – persists between calls.

Recursion

Finally a function is able to call itself. Here is one way to compute the factorial of a number:

func factorial(x uint) uint {

if x == 0 {

return 1

}

return x * factorial(x-1)

}factorial calls itself, which is what makes this function recursive. In order to better understand how this function works, lets walk through factorial(2):

Is

x == 0? No. (xis 2)Find the factorial of

x – 1Is

x == 0? No. (xis 1)Find the

factorialofx – 1Is

x == 0? Yes, return 1.

return

1 * 1

return

2 * 1

Closure and recursion are powerful programming techniques which form the basis of a paradigm known as functional programming. Most people will find functional programming more difficult to understand than an approach based on for loops, if statements, variables and simple functions.

Defer, Panic & Recover

Go has a special statement called defer which schedules a function call to be run after the function completes. Consider the following example:

package main

import "fmt"

func first() {

fmt.Println("1st")

}

func second() {

fmt.Println("2nd")

}

func main() {

defer second()

first()

}This program prints 1st followed by 2nd. Basically defer moves the call to second to the end of the function:

func main() {

first()

second()

}defer is often used when resources need to be freed in some way. For example when we open a file we need to make sure to close it later. With defer:

f, _ := os.Open(filename) defer f.Close()

This has 3 advantages: (1) it keeps our Close call near our Open call so it's easier to understand, (2) if our function had multiple return statements (perhaps one in an if and one in an else) Close will happen before both of them and (3) deferred functions are run even if a run-time panic occurs.

Panic & Recover

Earlier we created a function that called the panic function to cause a run time error. We can handle a run-time panic with the built-in recover function. recover stops the panic and returns the value that was passed to the call to panic. We might be tempted to use it like this:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

panic("PANIC")

str := recover()

fmt.Println(str)

}But the call to recover will never happen in this case because the call to panic immediately stops execution of the function. Instead we have to pair it with defer:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer func() {

str := recover()

fmt.Println(str)

}()

panic("PANIC")

}A panic generally indicates a programmer error (for example attempting to access an index of an array that's out of bounds, forgetting to initialize a map, etc.) or an exceptional condition that there's no easy way to recover from. (Hence the name “panic”)

Problems

sumis a function which takes a slice of numbers and adds them together. What would its function signature look like in Go?Write a function which takes an integer and halves it and returns true if it was even or false if it was odd. For example

half(1)should return(0, false)andhalf(2)should return(1, true).Write a function with one variadic parameter that finds the greatest number in a list of numbers.

Using

makeEvenGeneratoras an example, write amakeOddGeneratorfunction that generates odd numbers.The Fibonacci sequence is defined as:

fib(0) = 0,fib(1) = 1,fib(n) = fib(n-1) + fib(n-2). Write a recursive function which can findfib(n).What are defer, panic and recover? How do you recover from a run-time panic?

| ← Previous | Index | Next → |